Chantal Gibson

Biography

Photography by: Dale Northey

Author photo of Chantal Gibson in front of a slightly blurred background. Gibson is wearing a black shirt and loop earrings. Smiling, head and body turned slightly toward camera’s left.

Chantal Gibson is an award-winning writer-artist-educator living on the ancestral lands of the Coast Salish Peoples. Working in the overlap between literary and visual art, her work confronts colonialism head on, imagining the BIPOC voices silenced in the spaces and omissions left by systemic cultural and institutional erasure. Her visual art has been exhibited in museums and galleries across Canada and the US, most recently in the Senate of Canada building in Ottawa.

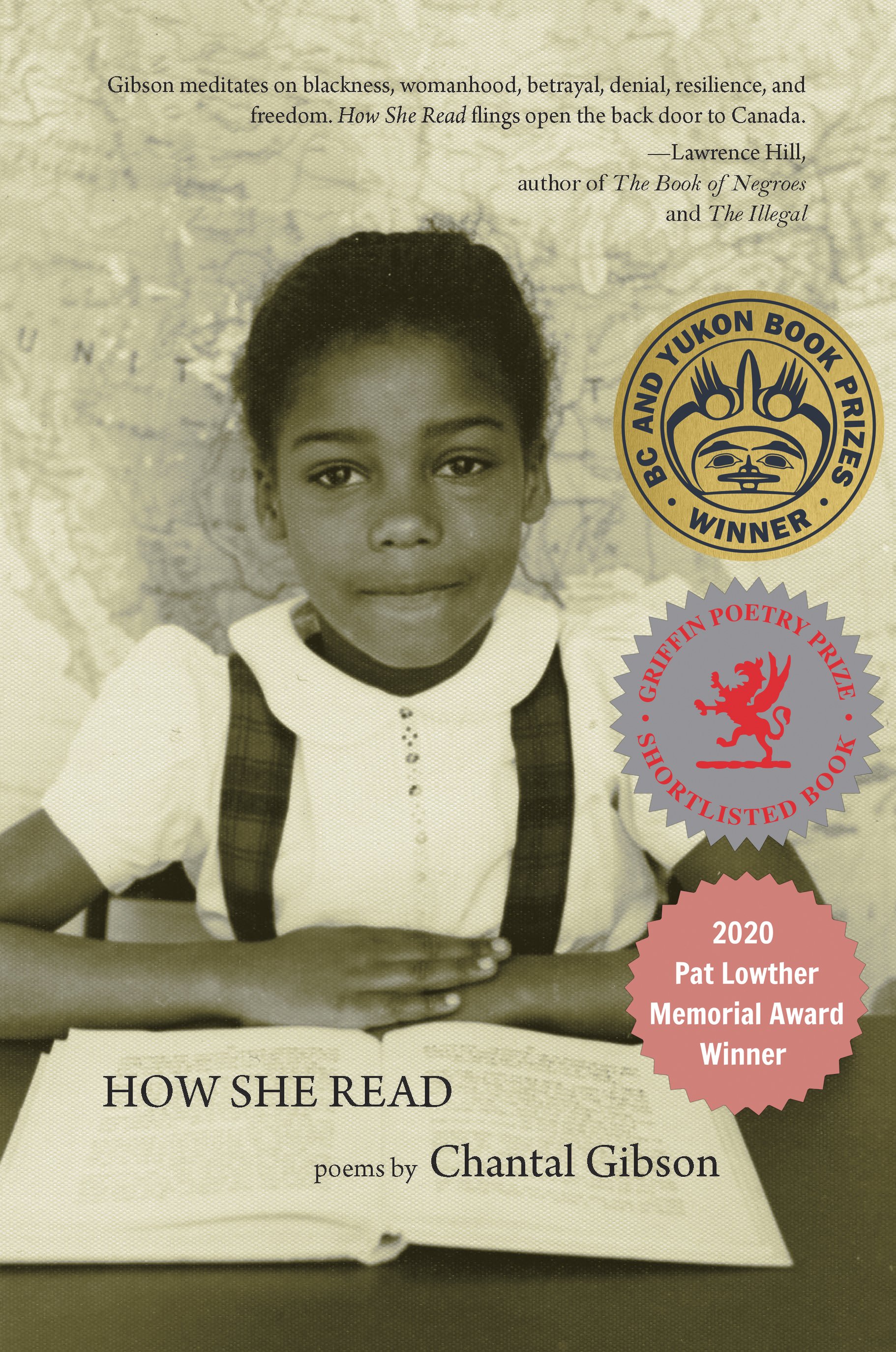

Gibson’s debut book of poetry, How She Read (Caitlin Press, 2019), was the winner of the 2020 Pat Lowther Memorial Award and the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize, a finalist for both the 2020 Griffin Poetry Prize and the inaugural Jim Deva Prize for Writing That Provokes. How She Read received second place for the Fred Cogswell Award for Excellence in Poetry, and was longlisted for the Nelson Ball Poetry Prize, the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award, and the Raymond Souster Award. Gibson’s work has been published in Canadian Art, The Capilano Review, The Literary Review of Canada, Room magazine and Making Room: 40 years of Room Magazine (Caitlin Press, 2017) and was longlisted for the 2020 CBC Poetry prize. Recipient of the prestigious 2021 3M National Teaching Fellowship, Gibson teaches writing and visual communication in the School of Interactive Arts & Technology at Simon Fraser University.

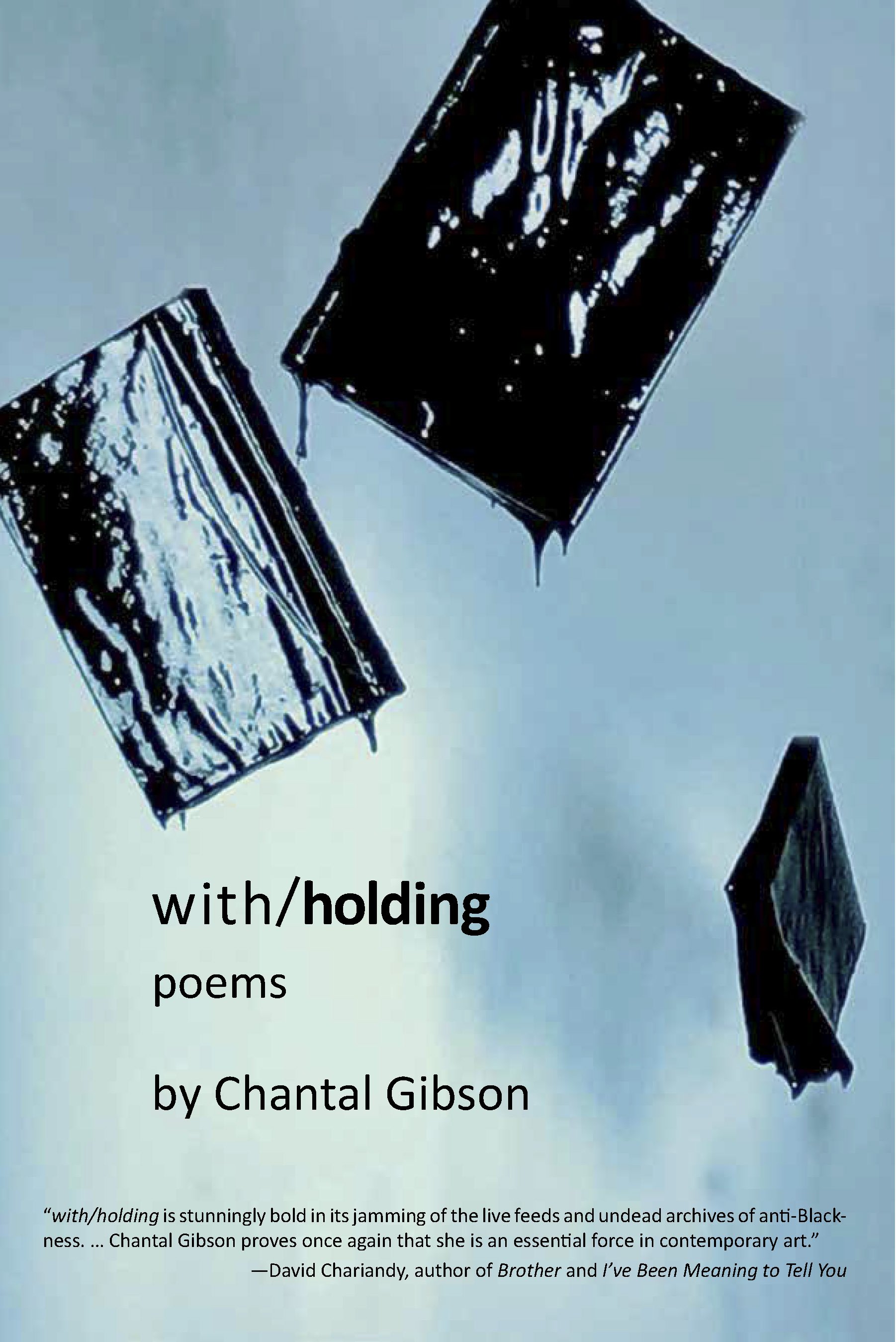

Gibson’s book with/holding (Caitlin Press, September 2021) is a follow-up to her award-winning debut and offers a collection of genre-blurring poems that examine the representation and reproduction of Blackness across communication media and popular culture. A meditation on the rise of falling monuments, in the wake of Add to Cart consumer culture, this collection draws on the language of brand marketing, news and social media, DIY culture and graphic design to confront the role of the new colonial machinery in the relentless consumption and commodification of Black bodies.

Poetics Statement

“Chantal Gibson’s work in How She Read (Caitlin Press, 2019) distinctly centers Black womanhood—addressing motherhood, daughterhood and being mixed race in Canada, highlighting the depth and duration of the imperialist ideas embedded in everyday things from CanLit to coloured pencils, from storybooks to postage stamps.

‘Both my written and visual work investigate the representation of Black people across the Canadian cultural landscape. My goal is to unpack mechanisms of power and systemic oppression and to create what I hope are interesting and compelling works that invite audiences to question the works as well as the institutions they function in.’ ”

Sample of Poet's Work

subordinate clause

because you were my first book

because yours was my first face

because your first look was sorrow

because your second was love

because I charted your scalp like an atlas,

sectioned your hair to the roots with the pointy tip

of a tail comb, discovered your pink secret

at the crown, and released the ancestral sighs

of fingertips and VO5

because I studied the slight coffee stain

on your side teeth right next to the fake one

in the front and the soft constellation of tiny

black moles on the rise of your right cheek

every time you smile

because I memorized the monthly swell of your

breasts and the water bloat of your ring

fingers, because I feared the dark potholed alleys

of your palms and the black slap of Jesus sandal

against my thigh

because she was your first book

because hers was your first face

because your first look was sorrow

because her first look was shame

because they called you ugly

because I am your spitting image

(because there are no honest poems

about dead women)

because I wrote every line twisted

in the furrow of your brow

pg. 31

How She Read

Section 1: grammar of loss

Note: In "subordinate clause" the quote “there are no honest poems/ about dead women” is from Audre Lorde’s poem of the same name, in Our Dead Behind Us. (New York: W.W. Norton,1986), 61.

Two poems from The Mountain Pine Beetle Suite

I. dendroctonus ponderosae

They come with axes between their teeth. Pioneer beetles,

females hungry for trees, ready to carve an instant town out

of the wilderness. Somewhere in the needling green sprawl

between Darwin & God, an edict etched deep & tingling

beneath the skin, they believe this stand of old pines will last

a lifetime. By nature, they desire. A species wants

nothing more than to procreate. Back home,

a pheromone-frenzy stirs a gnashing appetite

for industry. The new believers wake & uncross

their legs, hell-bent on leaving this unholy land

of hollow trees. How soon they forget the splinter’s prick

between their lips. In unison, they hum, the blue-

stained settlers, young males itching to leave this once-

Eden girdled & snap-necked. A ghost town rusting, their dead

pitched out of the trees. Meanwhile the humans look

petrified, like butterflies shocked in resin, arms wide,

palms flat against the front room window, disbelieving

the FOR SALE sign on the lawn, wishing away

the dust on the toys piled up in the driveway.

II. summer: mating season

the female plays house between

the bark & the sapwood she is

hardwired for love in the phloem

her scent on the walls she rubs

her Avon wrists together & waits

the male finds her intoxicated they

make love under the trees legs be-

come arms hands grow fingers nails

scratch tiny love notes in the bark

summer is short here little time

for courtship in the North: the cold-

blooded retreat to the woods veins

pumped with anti-freeze the female

bores deeper into the sapwood she

drags her smokes & her big belly up

the tree carves her birthing chamber

and her coffin with her teeth

pg. 58-59

How She Read

Section 2: icons

Homographs

1: a race with skin

pigmentation differ-

ent from the white

race (esp. Blacks);

You preferred coloured back then, stung less than

negro. Mulatto is dated. I’m mixed race now.

2: complexion tint,

a characteristic of

good health;

No one noticed the colour in your cheeks.

The Christmas dinner one-liner, ‘Must’ve been dirty,

it even made you blush!’ At least, you taught me how

to take a joke.

3: of interest, variety

and intensity;

Remember Cabbagetown? Our coloured beginnings,

the dress shop lady, the front door, my broken pointy

finger, you in your secretary dress chasing her in the

street. Girl, where you learn to fight like that?

4: to give a deceptive

explanation or excuse

for;

The lawyer argued you were coloured by your emo-

tions. Quite naturally, of course. What other reason

would you have to beat a white bitch down?

5: to modify or bias;

My world, coloured. Never has a child felt more loved,

more protected, more ashamed.

6: an outward or token

appearance or form that is

deliberately misleading;

You coloured your apology with the single mother

story of my one good eye. The white lady dropped

the charges.

7: of character, nature;

You said, wait long enough, you’ll see their true colours.

I never told you she smiled at me as she turned away,

or that I stuck my finger in the hinge just to see what

would happen.

pg. 24

How She Read

Section 1: the grammar of loss

Introduction to Cultural Studies (for EJ)

You used to sit with me while I’d take a bath, til

you were about eleven, chat and count the Avon

bath beads you gave me for Christmas. I doubt

it ever occurred to you that a woman with three

kids might want a little time alone. For a while,

you’d always bring some book or magazine,

Judy Bloom, Nancy Drew, some Teen Beat

Tiger Beat foolishness with white boys on it,

the Toronto Star, the Sears catalogue, a World

Book Encyclopedia—but, you wouldn’t read

them to me, you’d just tell me about what you’d

learned, if you liked them or not—always white

pieces of blue-lined three ring binder paper torn

and placed between the pages you prepared to

discuss. When you preferred that Sean Cassidy

over his brother David, I asked what coloured

boys did you like, but you couldn’t think of any,

except for Michael Jackson. But you didn’t like

him in that way. When the Beatles invaded in

‘64, I didn’t like Sam Cooke in that way, either.

I remember ’77, the summer of Emanuel Jaques,

The Shoe Shine Boy found dead on a rooftop in a

garbage bag. I nearly wept when you asked me

about Yonge St., faggots, body rubs, as if I’d know

how those child raping degenerates could drown

a young boy in a sink. You Scotch taped the Star

clippings in saran wrap, careful to keep them dry.

When you said, Mom, only poor kids get lured away

and snatched in bags, I understood your insistence

and stopped reading your sisters Curious George.

Sometimes, I’d watch you watching me, your gaze:

water beads in my fro, my big boobs floating in the

fake lavender scented water, my pink C-section scar,

the wiry hair between my legs, like you were trying

to figure me out, like you were trying to see the future.

pg.35

How She Read

Section 2: icons

Note: In "An Introduction to Cultural Studies," I am referencing Emanuel Jacques, a kid I didn’t know, who was found murdered in Toronto in August 1977. I was ten and consumed with newspapers. Twenty years ago, I read the same stories on microfiche. Now, I Google them. There are some things you can’t get over.

How She Read: https://caitlin-press.com/our-books/how-she-read/

with/holding: https://caitlin-press.com/our-books/with-holding/